The Lost Art of Deadline Writing

A new anthology of sportswriting celebrates the poetry written in the press box.

Bap. That’s how Damon Runyon, reporting on Game 1 of the 1923 World Series, Giants versus Yankees, for the New York American, records the sound of Casey Stengel connecting with a pitch from “Bullet Joe” Bush. Bat meets ball, the essential atomic encounter—and Runyon puts the sound of it, the briefest, most prodigious syllable, right in the center of his column. Everything leads to it, everything spins out of it. Bap! Writers, those nonjocks, know this moment too. Put the right word in the right place, make the connection, and there’s a perceptible sweetness of impact. Stadiums do not rise when it happens, earthly crowds do not roar, but at your desk or your wobbling perch in Starbucks you feel it: silent terraces of angels pumping their fists.

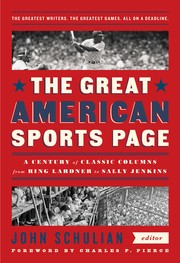

The surprise and delight of The Great American Sports Page, John Schulian’s selections from a century’s worth of newspaper columns about baseball, boxing, football, gymnastics, and (in one case) swimming the English Channel, is how often it happens—how often the writers connect, how often the prose approaches the condition of flat-out poetry. The brilliant hard-boiled lyricism of Sandy Grady, in 1964, as he watches a crowd of Phillies fans after a home loss: “They hit the sidewalk with tight mouths, like people who had seen a train hit a car.” Or Joe Palmer, in 1951, summoning a vision of the racehorse Man o’ War in motion: “Great chunks of sod sailed up behind the lash of his power.” Sailed up: The soft swell of the verb puts us into slow motion. And the lash of his power: the conceit that Man o’ War, no doubt well acquainted with the ministry of the crop, is scourging the earth itself with loops of horse-voltage. Bap, bap, and bap again.

Even the high bombast of Grantland Rice, who as Schulian notes “seemed to see every event he covered as the equivalent of the Trojan War,” has a ring of nobility to it, a straining for epic attainments. That stuff is largely gone now. No more the voice of the bard, doing his solo, sobbing and exalting: Sports commentary in 2019 is forensic, polyphonic, multiplatformed. Compare for example Rice’s quivering hyperbole—“There was never a ball game like this before, never a game with as many thrills and heart throbs strung together in the making of drama that came near tearing away the soul to leave it limp and sagging, drawn and twisted out of shape”—with the laser-edged nitty-gritty of a writer like Bill Barnwell, as he digs into Super Bowl LIII for ESPN.com:

Teams that load up on twists often struggle to keep contain or leave an obvious running lane open for the opposing quarterback, but the Patriots did an excellent job of getting pressure against the interior of the Rams’ line (particularly guard Austin Blythe) while simultaneously closing down Goff when he bootlegged out of the pocket.

This is a different kind of poetry, generated out of the hidden matrix of a game, the deep jargon. (It uses GIFs to make its points.) Will we still be digging it in 100 years?

The better and crazier writing in Schulian’s book—the writing that twangs loudest with idiosyncrasy, experience, style—is indeed the oldest, from the 1910s, ’20s, ’30s, ’40s. It’s rather thrilling, actually, the extent to which these smoking, snarling, hat-tipped-back word mechanics were making their own rules. Ring Lardner in 1921 turns in a whole column, in his personalized American-primitive idiom, about his editor not letting him report on football: “I don’t want to be no kill joy but I can’t resist from telling you what a treat you missed this fall namely I was going to write up some of the big games down east but at the last minute the boss said no.” Heywood Broun, by contrast, is an effortlessly glittering highbrow. At Madison Square Garden in 1922, he finds the boxing style of Rocky Kansas to be “as formless as the prose of Gertrude Stein.” Kansas is fighting the crisply traditional Benny Leonard, an exemplary pugilist. A Leonard defeat, declares Broun, would give aid to the forces of “dissonance, dadaism, creative evolution and bolshevism.”

And they were on deadline! We’re all on deadline, of course, at all times and in all places. The last judgment, as Kafka pointed out, “is a summary court in perpetual session.” But a print deadline—the galloping clock, the smell of the editor—is a particular concentration of mortal tension. The brain on deadline does whatever it can: It improvises, it compresses, it contrives, it uses the language and the ideas that are at hand. Inspiration comes or it doesn’t. Here the writer is an athlete—performing under pressure and, if he or she is good, delivering on demand.

It was Ernest Hemingway, once of The Kansas City Star, who turned deadline prose into a modernist art, and Papa’s prints are all over The Great American Sports Page. Jimmy Cannon goes on a fishing trip with Joe DiMaggio near the end of his run with the Yankees and winds up writing, basically, a passage from The Old Man and the Sea. “Joe said: ‘Watch out. It’s going to break water.’ The sail fish came up out of the sun-burnished sea in a flapping leap. It went up straight gleaming and quivering and then it was gone.” W. C. Heinz in “Death of a Racehorse” witnesses the on-track destruction of Air Lift, “son of Bold Venture, full brother of Assault.” His account has an ecstatic spareness to it. Emotion is rigorously excluded, à la Hemingway—which means it is everywhere, and overwhelming.

There was a short, sharp sound and the colt toppled onto his left side, his eyes staring, his legs straight out, the free legs quivering.

‘Aw—’ someone said.

That was all they said.

The influence attenuates over the decades, but it never goes away. Sally Jenkins, in 2001, writes about race-car drivers like Hemingway wrote about bullfighters: “It’s beyond a philosophy, or a faith, it’s simply as essential to them as breathing. They are consumed to ashes with the idea that if you give nothing, you get nothing.”

(Jenkins is one of just three women writers included in Schulian’s book, alongside 43 men. This ratio may accurately reflect the gender breakdown of newspaper sportswriting over the past 100 years. But it looks ridiculous; it is ridiculous. Wouldn’t a Library of America anthology have been the perfect occasion to find a way to even things up?)

Sport is not like life. It’s the hit, the punch, the shot, the stroke, the break—the consecrated instant that lasts forever. Bap! As commentary disperses itself across in-game tweets and postgame podcasts, and as our analysis of what actually happened gets more granular, more expert, less Runyon-esque, are we losing touch with the moment of contact? The clattering presses are falling silent; the internet gapes, demanding content from every angle. (“Content,” groans the veteran sportswriter Charles P. Pierce in his foreword to The Great American Sports Page. “Lord how I hate that goddamn word.”) So farewell, perhaps, to the gymnasts of deadline prose, the ones who stuck the landing. They were mighty in their day.

There’s a photo of Bob Ryan, a sports reporter for The Boston Globe, sitting at the press table at the Boston Garden in the ’70s, surrounded by admiring Celtics fans. They’re all staring over his shoulder, at his Olivetti Lettera 32 typewriter, into which—grandly, performatively, a pencil between his teeth—he is rolling a fresh sheet of paper. Sportswriting as public art: Ryan sits in a bubble of awe, with a hint of the Dionysian about him. He looks, in this picture, like a better-groomed Lester Bangs. He looks artistic, and equal to the challenge before him. And the people are staring, I’ll say it again, at his typewriter—at what he is about to write.

This article appears in the May 2019 print edition with the headline “Poets in the Press Box.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.